The development of venous thromboembolism (VTE) is one of the major consequences observed in patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), in both normal and in critically ill patients. The latter are at an even higher risk due to immobility, the systemic inflammatory state, the presence of mechanical ventilation and central venous catheters, all of which contribute to VTE risk within intensive care units.

A general VTE risk stratification for hospitalized patients with COVID-19 is recommended. Patients belonging to the following groups should receive standard pharmacological VTE prophylaxis (unless evident contraindications):

- Those with respiratory failure or co-morbidities (e.g., active cancer or heart failure)

- Those who are bedridden

- Those requiring intensive care

Which type of prophylaxis is suggested in COVID-19 patients at risk for VTE?

The general guidelines for VTE management are the best choice and the recommendations are as follows:

- Daily use of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH)1,2

- Twice daily subcutaneous injection of unfractionated heparin3

- Intermittent pneumatic compression3

Since the optimal dosing in patients with severe COVID-19 remains unknown and requires further investigation, clinicians are debating the possibility of using different doses (intermediate dose or full therapeutic dose) for routine care of patients with COVID-19.

VTE prophylaxis is likely to be continued for discharged patients and either LMWH4 or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs)5,6 should be considered. Unfortunately, the lack of specific indications in COVID-19 settings may put some patients at risk of bleeding7 and clinicians should, therefore, carefully evaluate the patient characteristics (prolonged immobilization) and comorbidities (active cancer) to decide for the most appropriate treatment.

The use of advanced VTE therapies such as catheter-directed therapies during the current outbreak should be limited to the most critical situations.

The increased risk for VTE events may also be the result of the peculiar situation occurring during diagnosis at the time of COVID-19: to reduce the risk of cross-infections, the usual imaging studies performed to investigate for VTE are drastically reduced, causing an underestimation of the real cases.

Some unique considerations must be thought out for critically ill patients in intensive care units. As already reported, they are at even higher risk for developing VTE as alteration in several physiological pathways, such as pharmacokinetics, may require anticoagulation dose adjustment.8 In these cases, parenteral anticoagulation is the first choice of intervention.

Acute coronary syndrome in COVID-19 patients is recommended to be treated with dual antiplatelet therapy and full-dose anticoagulation,9,10 with a special attention to patients at high risk of bleeding. For such patients, the administration of less potent antiplatelet agents, such as clopidogrel, has to be considered.

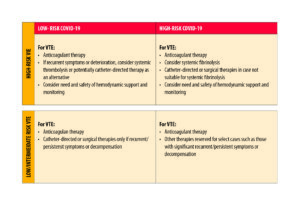

For an algorithm to give a general indication of type of interventions based on risk due to VTE and COVID-19 severity, see Figure 1 (adapted from) 11.

References

- Schünemann HJ, Cushman M, Burnett AE, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized medical patients. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3198‐3225. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2018022954

- Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e195S‐e226S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2296

- World Health Organization. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infection is suspected. Interim guidance 28 January 2020. Accessible at: https://www.who.int/docs/defaultsource/coronaviruse/clinical-management-of-novel-cov.pdf.

- Hull RD, Schellong SM, Tapson VF, et al. Extended-duration venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients with recently reduced mobility: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(1):8‐18. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-153-1-201007060-00004

- Cohen AT, Harrington RA, Goldhaber SZ, et al. Extended thromboprophylaxis with betrixaban in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(6):534‐544. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1601747

- Spyropoulos AC, Lipardi C, Xu J, et al. Modified IMPROVE VTE risk score and elevated D-dimer identify a high venous thromboembolism risk in acutely ill medical population for extended thromboprophylaxis. TH Open. 2020;4(1):e59‐e65. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1705137

- Schindewolf M, Weitz JI. Broadening the categories of patients eligible for extended venous thromboembolism treatment. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(1):14‐26. doi:10.1055/s-0039-3400302

- Smith BS, Yogaratnam D, Levasseur-Franklin KE, Forni A, Fong J. Introduction to drug pharmacokinetics in the critically ill patient. Chest. 2012;141(5):1327‐1336. doi:10.1378/chest.11-1396

- Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130(25):2354‐2394. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000133

- Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(2):119‐177. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393

- 11. Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;S0735-1097(20)35008-7. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2