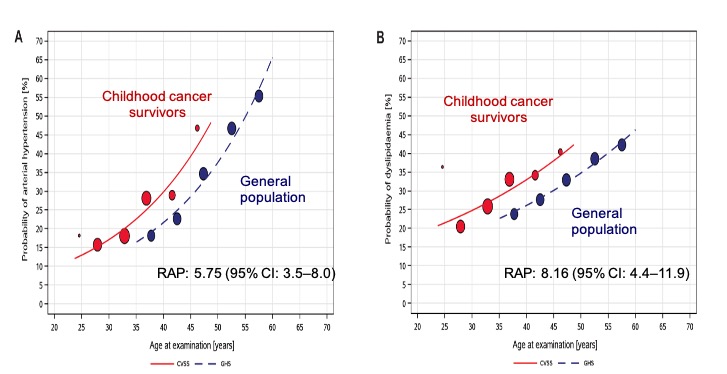

Continued rapid advancement in cancer treatment and early cancer detection have resulted in a steady growth of the population known as long-term cancer survivors. In the USA only, epidemiological projections estimated that there will be 26 million cancer survivors by the year 2040, representing a 68% increase for the period between 2016 and 2040 [1]. For childhood cancer survivors in Europe, the estimated number of survivors aged between 25 and 29 years is currently approximately 500,000 survivors with an increasing number each year of an additional 10,000 new survivors [2]. However, despite these improvements, cancer cure is not without life-long consequences and, at least 60% of cancer survivors develop health-related adverse events later in life. This vulnerable population faces an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, the most frequent non-malignant cause of morbidity and mortality in this population. Cardiotoxicity related to chemotherapy and radiotherapy accounts for part of this increased risk [3]. The magnitude of risk and manifestations in these individuals are influenced by numerous other reasons including tumor- and host-related factors [4].

The latest research has shown that many survivors are unaware of possible late effects and health risks from their history of cancer. It has been also reported that, in general, medical practitioners lack sufficient information regarding pathophysiology and natural courses of treatment-related complications [11]. Considering that the experiences of long-term cancer survivors vary within and particularly between countries, an International Guideline Harmonization Group was initiated to optimize and harmonize the recommendations for surveillance of late effects worldwide [12]. In this line of efforts, the “Survivorship passport” has been recently launched as important tool to provide all childhood cancer survivors from European region with optimal long-term care (for more information, please refer also to http://www.survivorshippassport.org/). The Survivorship Passport is a document aimed to provide each childhood cancer survivor with an electronic summary, including individualized recommendations for follow-up, as well as respective translations in European languages. This document will accompany the patient through the transition from pediatric to adult healthcare or in the case of moving to another country, allowing the individual to keep a precise record of the past therapies and informing future medical practitioners. The passport should meet international criteria and be easily understood and accessible to physicians of different European regions. It should be available both in paper and digital format and contain information in lay terms, to facilitate an understanding by survivors as well. The advantages of this system are multiple: it can provide a more homogeneous follow-up and screening of all European young cancer survivors, resulting in more efficient use of healthcare systems’ economic resources by avoiding unnecessary examinations. The final goal will be to improve the personal, socioeconomic and psychosocial burden of all the childhood cancer survivors [13].

A lifelong follow-up and cardiovascular protection are clearly indicated in cancer survivors, both long-term survivors of an adult and childhood cancer. Further research is also needed to ascertain its benefit.

References

- Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH. Anticipating the “silver tsunami”: prevalence trajectories and comorbidity burden among older cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2016;25(7):1029-1036.

- Hjorth L, Haupt R, Skinner R, et al. Survivorship after childhood cancer: PanCare: a European Network to promote optimal long-term care. Eur J Cancer 2015;51(10):1203-1211.

- Mulrooney DA, Yeazel MW, Kawashima T, et al. Cardiac outcomes in a cohort of adult survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: retrospective analysis of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. BMJ 2009;339:b4606.

- Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer (PDQ®): Health Professional Version. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. Bethesda, MD, USA (2002).

- Faber J, Wingerter A, Neu MA, et al. Burden of cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular disease in childhood cancer survivors: data from the German CVSS-study. Eur Heart J 2018;39(17):1555-1562.

- Hudson MM, Oeffinger KC, Jones K, et al. Age-dependent changes in health status in the Childhood Cancer Survivor cohort. J Clin Oncol 2015;33(5):479-491.

- Lipshultz SE, Lipsitz SR, Mone SM, et al. Female sex and higher drug dose as risk factors for late cardiotoxic effects of doxorubicin therapy for childhood cancer. N Engl J Med 1995;332(26):1738-1743.

- Panova-Noeva M, Neu MA, Eckerle S, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors are important determinants of platelet-dependent thrombin generation in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Clin Res Cardiol 2019;108(4):438-447.

- Svilaas T, Lefrandt JD, Gietema JA, Kamphuisen PW. Long-term arterial complications of chemotherapy in patients with cancer. Thromb Res. 2016;140(Suppl 1):S109-118.

- Panova-Noeva M, Schulz A, Arnold N, et al. Coagulation and inflammation in long-term cancer survivors: results from the adult population. J Thromb Haemost 2018;16(4):699-708.

- Salz T, McCabe MS, Onstad EE, et al. Survivorship care plans: is there buy-in from community oncology providers? Cancer 2014;120(5):722-730.

- Kremer LC, Mulder RL, Oeffinger KC, et al. A worldwide collaboration to harmonize guidelines for the long-term follow-up of childhood and young adult cancer survivors: a report from the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60(4):543-549.

- Haupt R, Essiaf S, Dellacasa C, et al. The ‘survivorship passport’ for childhood cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer 2018;102:69-81.