Value and limitations of low-molecular-weight heparins

Following the demonstration that vitamin K antagonists (VKA) are of limited value for the treatment of venous thromboembolic (VTE) disorders occurring so frequently in the follow-up of patients with cancer [1], several randomized clinical trials have consistently shown that the use of therapeutic doses of low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWHs) is more effective than and as safe as VKA for the treatment of patients with cancer-associated thrombosis (CAT) [2]. However, the rate of recurrent VTE occurring in patients randomized to LMWH in these clinical trials (ranging between 7% and 9%) [3,4] was found to exceed by a large amount than expected in the clinical course of cancer-free patients with VTE (1.5–3%) treated with conventional anticoagulants [5]. In addition, in a recent European prospective cohort study addressing the 6-month follow-up of approximately 400 consecutive patients with CAT who had been treated with therapeutic doses of commercially available LMWHs, the rate of recurrent VTE was found to be remarkably high (8.1%; 95% CI: 5.4–11%) [6]. As the rate of major bleeding complications arising in this investigation (8.3%) was found to be high as well, the cumulative incidence of LMWH discontinuation owing to either recurrent VTE or major bleeding approached 20% [6]. Accordingly, there is a substantial room for improvement, especially if we consider that the long-term use of heparins is associated with a considerable burden for patients and cost for healthcare systems [7], and shares with most available parenteral drugs the unavoidable risk of decline in the patients adherence and persistence [8].

The new era: the direct oral anticoagulants

Following the promising results displayed by the novel drugs in comparison to VKAs in the subgroup of cancer patients randomized to either treatment group in several clinical investigations [5], four randomized clinical trials have recently addressed the value of direct oral factor Xa inhibitors in comparison to the conventional LMWH treatment in cancer patients with acute VTE: edoxaban in the HOKUSAI-K study [9], rivaroxaban in the SELECT-D [10], and apixaban in the ADAM VTE [11] and CARAVAGGIO [12] studies. The differences in the study designs among the four clinical trials were marginal. In each study, patients with (either symptomatic or accidentally detected) CAT free from contraindications to anticoagulant therapy were randomized to receive, for (at least) 6 months, subcutaneous administration of dalteparin according to the CLOT strategy (e.g., 200 IU/kg once daily for 1 month followed by ¾ of the initial dose) [3] or the respective direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) in full, unmonitored, oral doses: from the beginning of treatment when the tested drug was rivaroxaban [10] or apixaban [11,12], and after at least 5 days of heparin when edoxaban was assessed [9]. In all studies, the rate of (objectively proven) symptomatic recurrent VTE and that of major bleeding complications occurring during the study period was recorded. While in the SELECT-D, ADAM VTE and CARAVAGGIO studies, the efficacy and safety endpoints were calculated separately at the end of the first 6 months [10-12], in the HOKUSAI-K study the primary endpoint was an aggregation of recurrent VTE and major bleeding at the end of 1 year, irrespective of the duration of treatment [9].

In all four clinical trials, the primary endpoint (non-inferiority of the tested DOAC in comparison to dalteparin) was unequivocally achieved [9-12]. However, while in each of them a strong trend favoring the tested DOAC in terms of recurrent VTE during the predefined study period was observed, the bleeding risk diverged. Indeed, no difference was seen between apixaban and dalteparin in the ADAM VTE and CARAVAGGIO studies [11,12], whereas a higher rate of bleeding was observed in patients who were prescribed edoxaban and rivaroxaban in the HOKUSAI-K [9] and SELECT-D [10] studies, respectively. Of interest, in a post-hoc analysis of the latter studies, the excess in the bleeding risk was almost entirely imputable to the rate of gastrointestinal events occurring in patients with gastrointestinal cancer [9,10]. However, because of the relatively low number of patients with gastrointestinal cancer recruited in the four studies, the interpretation of these findings requires caution. Of interest, the incidence of urogenital bleeding was also consistently increased across the four studies among patients allocated to the DOAC treatment.

In summary, in comparison to LMWH the use of factor Xa inhibitors for the treatment of CAT is likely to reduce the risk of symptomatic recurrent VTE, making it comparable to that expected in the treatment of VTE disorders in patients free from malignancy [5], with an acceptable increase in the bleeding risk.

Meta-analyses of the clinical trials addressing the value of DOACs

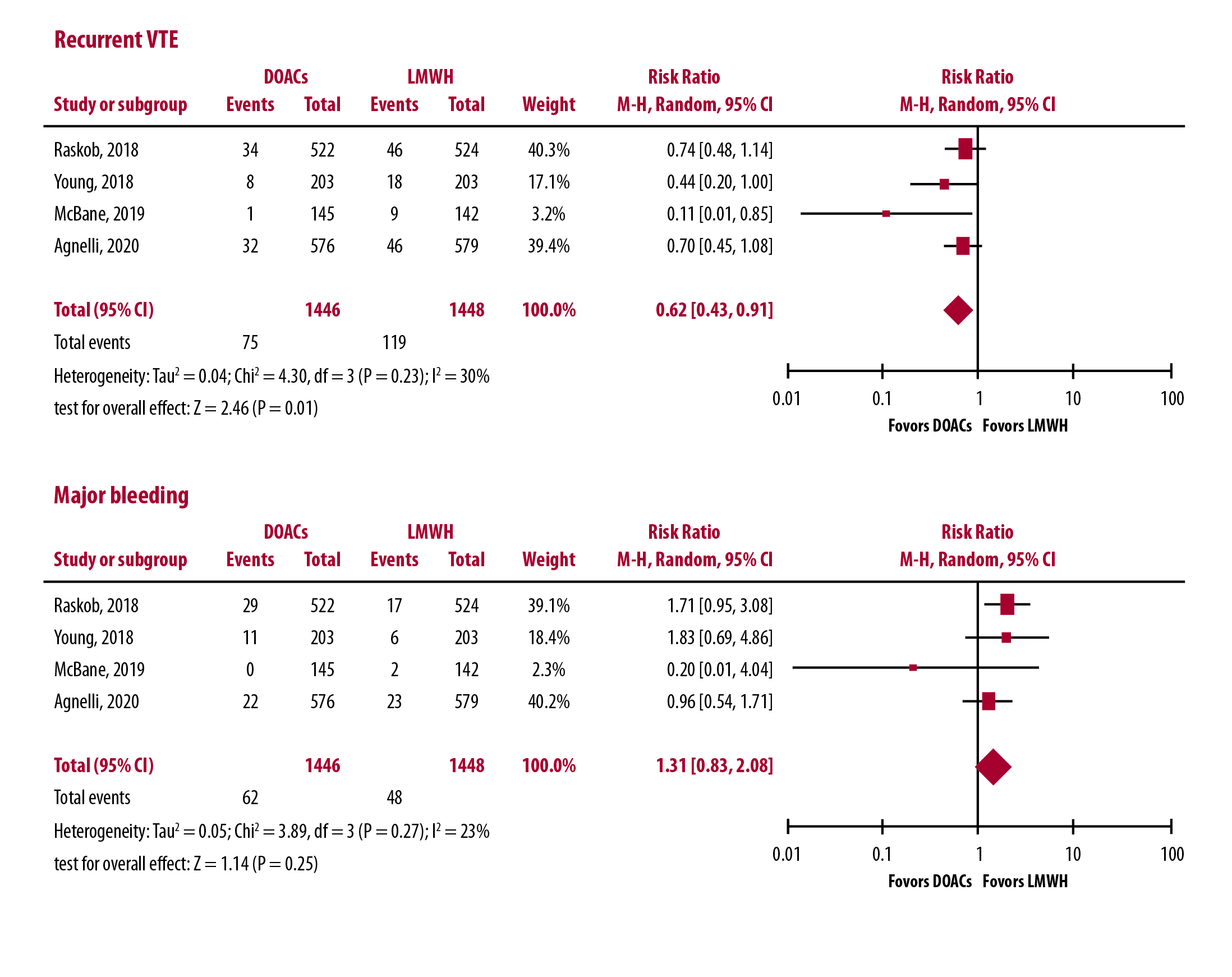

In order to achieve stronger conclusions, two meta-analyses of the available clinical trials have recently been conducted and published [13,14]. In the former, which excluded the results of the ADAM VTE, a total of 2,607 patients were included [13]. Although the risk of recurrent VTE in patients on DOAC treatment was found to decrease by more than 30% in comparison to dalteparin recipients, the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (relative risk [RR]: 0.68; 95% CI: 0.39–1.17). Conversely, the risks of major bleeding in the DOAC patients (RR: 1.36; 95% CI: 0.55–3.35) was non-significantly higher.

It is evident that the broader the number of patients analyzed the higher the advantage of the factor Xa inhibitors over dalteparin for prevention of recurrent symptomatic VTE in the treatment of CAT. It is noteworthy that the incidence of events occurring in the dalteparin arms (more than 8%) fully overlaps that found in previous studies [2-4,6], and that the incidence of events occurring in the DOACs recipients (just more than 5%) approximates that expected in cancer-free patients with VTE [5]. However, in each study, the superiority of the tested DOAC over LMWH became more evident after the first month of therapy, most likely as a direct consequence of the 25% reduction in the dalteparin dosage, the therapeutic program was dictated by available guidelines. Administering higher doses of dalteparin in the remaining 5 months could have increased the hemorrhagic risk.

Implications for clinical practice

Based on the results of the four available comparative trials, virtually all international guidelines now recommend the treatment of CAT with one of the three factor Xa inhibitors, provided patients are not perceived as being at a higher hemorrhagic risk. This is especially true of patients with cancer involving the gastrointestinal and the urogenital tract. Indeed, the results of trials addressing the value of apixaban are not (yet) reputed strong enough to encourage the use of this medication in patients with gastrointestinal cancer.

Notwithstanding, several indications remain for LMWH. Indeed, all patients in whom the DOACs are unsuitable or are contraindicated should receive a LMWH parenteral treatment, as should patients who will eventually develop VTE recurrence while on DOAC treatment. This is particularly important for patients with renal or liver failure, as well as for those with thrombocytopenia, in whom the availability of flexible drugs, such as the LMWHs, represent a precious resource. In addition, although the issue of the drug–drug interaction is not yet fully understood, a few antineoplastic drugs are likely to interfere with the DOACs making the association clinically dangerous [15].

Once patients are given a DOAC treatment, the problem of the optimal dose and duration sooner or later arises. While available evidences strongly discourage drug discontinuation in the absence of contraindications [16], lowering the dose is an option to be considered in the long-term follow-up of surviving patients. An international randomized clinical trial (the APICAR study) is currently ongoing, addressing the value of preventive versus therapeutic doses of apixaban beyond the first 6 months in patients with CAT. Meanwhile, in our opinion it is reasonable to consider the use of lower doses beyond the first 6 months in those patients in whom the cancer prognosis has improved, so that they do not require any further antineoplastic treatments.

References

- Prandoni P, Lensing AWA, Piccioli A, et al. Recurrent venous thromboembolism and bleeding complications during anticoagulant treatment in patients with cancer and venous thrombosis. Blood 2002;100(10):3484-88.

- Carrier M, Prandoni P. Controversies in the management of cancer-associated thrombosis. Expert Rev Hematol 2017;10(1):15-22.

- Lee AY, Levine MN, Baker RI, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin versus a coumarin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med 2003;349(2):146-53.

- Lee AYY, Kamphuisen PW, Meyer G, et al. Tinzaparin vs warfarin for treatment of acute venous thromboembolism in patients with active cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015;314(7):677-86.

- van Es N, Coppens M, Schulman S, Middeldorp S, Büller HR. Direct oral anticoagulants compared with vitamin K antagonists for acute venous thromboembolism: evidence from phase 3 trials. Blood 2014;124(12):1968-75.

- van der Wall SJ, Klok FA, den Exter PL, et al. Continuation of low-molecular-weight heparin treatment for cancer-related venous thromboembolism: a prospective cohort study in daily clinical practice. J Thromb Haemost 2017;15(1):74-79.

- Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest 2016;149(2):315-52.

- Khorana AA, McCrae KR, Milentijevic D, et al. Current practice patterns and patient persistence with anticoagulant treatments for cancer-associated thrombosis. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 2017;1(1):14-22.

- Raskob GE, van Es N, Verhamme P, et al. Edoxaban for the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2018;378(7):615-24.

- Young AM, Marshall A, Thirlwall J, et al. Comparison of an oral factor Xa inhibitor with low molecular weight heparin in patients with cancer with venous thromboembolism: results of a randomized trial (SELECT-D). J Clin Oncol 2018;36(20):2017-23.

- McBane RD 2nd, Wysokinski WE, Le-Rademacher JG, et al. Apixaban and dalteparin in active malignancy-associated venous thromboembolism: the ADAM VTE trial. J Thromb Haemost 2020;18(2):411-21.

- Agnelli G, Becattini C, Meyer G, et al. Apixaban for the treatment of venous thromboembolism associated with cancer. N Engl J Med 2020;382(17):1599-607.

- Mulder FI, Bosch FTM, Young AM, et al. Direct oral anticoagulants for cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood 2020 [Epub ahead of print]

- Giustozzi M, Agnelli G, Del Toro-Cervera J, et al. direct oral anticoagulants for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism associated with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost 2020 [Epub ahead of print]

- Riess H, Prandoni P, Harder S, Kreher S, Bauersachs R. Direct oral anticoagulants for the treatment of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: Potential for drug-drug interactions. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2018;132:169-79.

- Prins MH, Lensing AWA, Prandoni P, et al. Risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism according to baseline risk factor profiles. Blood Adv 2018;2(7):788-96.