Incidental venous thromboembolism (VTE) refers to any case of deep venous thromboembolism or pulmonary embolism (PE) discovered accidentally, mainly during a computer tomography scan to which the patient is subjected for other reasons. In many cases, these scans are performed to check the state of a tumor during routine follow-up visits. Therefore, incidental VTE is frequently part of the cancer-associated thrombosis experience. Despite the use of the term “incidental” these episodes can be associated with symptoms, even though their clinical onset is not suspected [1].

The reliability of the diagnosis of incidental PE (iPE) has increased over time, due to improved technology, which assures a better visualization of the pulmonary arteries during screening [2]. The iPE is reported to occur in 5% of cancer patients [3]. As in patients with a diagnosis of PE, patients with iPE must be accurately evaluated and stratified for the best treatment, as this diagnosis does not imply a less severe outcome even when specific symptoms are absent. Evidence shows that the presence of symptoms may play a critical role in the prognosis [4].

The current guidelines for anticoagulant treatment are the same for both PE and iPE, given the similar risks of mortality and adverse events registered (recurrent VTE, bleeding) between the two groups of patients [5]. Major attention should be paid to the risks and the consequences of iPE in cancer patients, as cancer itself is a predictor of a bad prognosis for PE [6]. In this light, some studies aimed to identify the important clinical features, the best treatment, the short- and long-term outcomes of cancer patients with iPE and a possible index to predict complications in this setting [7–10] and to improve patients’ safety and the decisions of physicians in clinical practice.

All these studies, although considering slightly different cohorts of patients and type of outcome, agree with the importance of a prompt therapeutic intervention in patients with iPE, which should compromise the possibility for outpatient care with the best safety management.

A large retrospective case−control study carried out at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center between 2006 and 2016, involving 904 confirmed cases of iPE in cancer, showed that the occurrence of iPE is associated with poor short- and long-term survival outcomes and highlighted some points [7]:

- Diagnosis occurred within the first year of cancer diagnosis;

- Chemotherapy is associated with a threefold higher risk of presentation of iPE;

- Only 20% of the patients with iPE showed specific symptoms;

- The most common medication prescribed for anticoagulant treatment was low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH; 88% of the discharged patients).

Another report, a prospective observational multicenter study involving centers in Europe and North America between 2012 and 2017, which included 695 patients with iPE and active cancer, analyzed the treatments to which the patients were subjected and the respective clinical outcomes over a 12-month follow-up period [8]. This study evaluated the incidence of subsegmental vs segmental, lobar or central PE and compared the risk of bleeding between prophylactic and intermediate dose, and therapeutic anticoagulation regimens. Authors concluded that the risk of recurrent VTE was comparable between patients with subsegmental and more proximal PE [8], thus supporting the adoption of anticoagulation treatment in patients with iPE (LMWH for most patients). Notwithstanding, the patients presented a similar risk of major bleeding irrespective the anticoagulation treatment. This result favors the debate about the type of treatment in cases of subsegmental iPE: the current suggestion from the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) is to tailor the treatment according to each single case, taking into account the risk of VTE and bleeding, the patient requests and needs, and the performance status. In addition, a meticulous review of the case with an expert chest radiologist, checking the quality of the diagnostic CT, is mandatory. Some iPEs may be artifacts, with no real meaning.

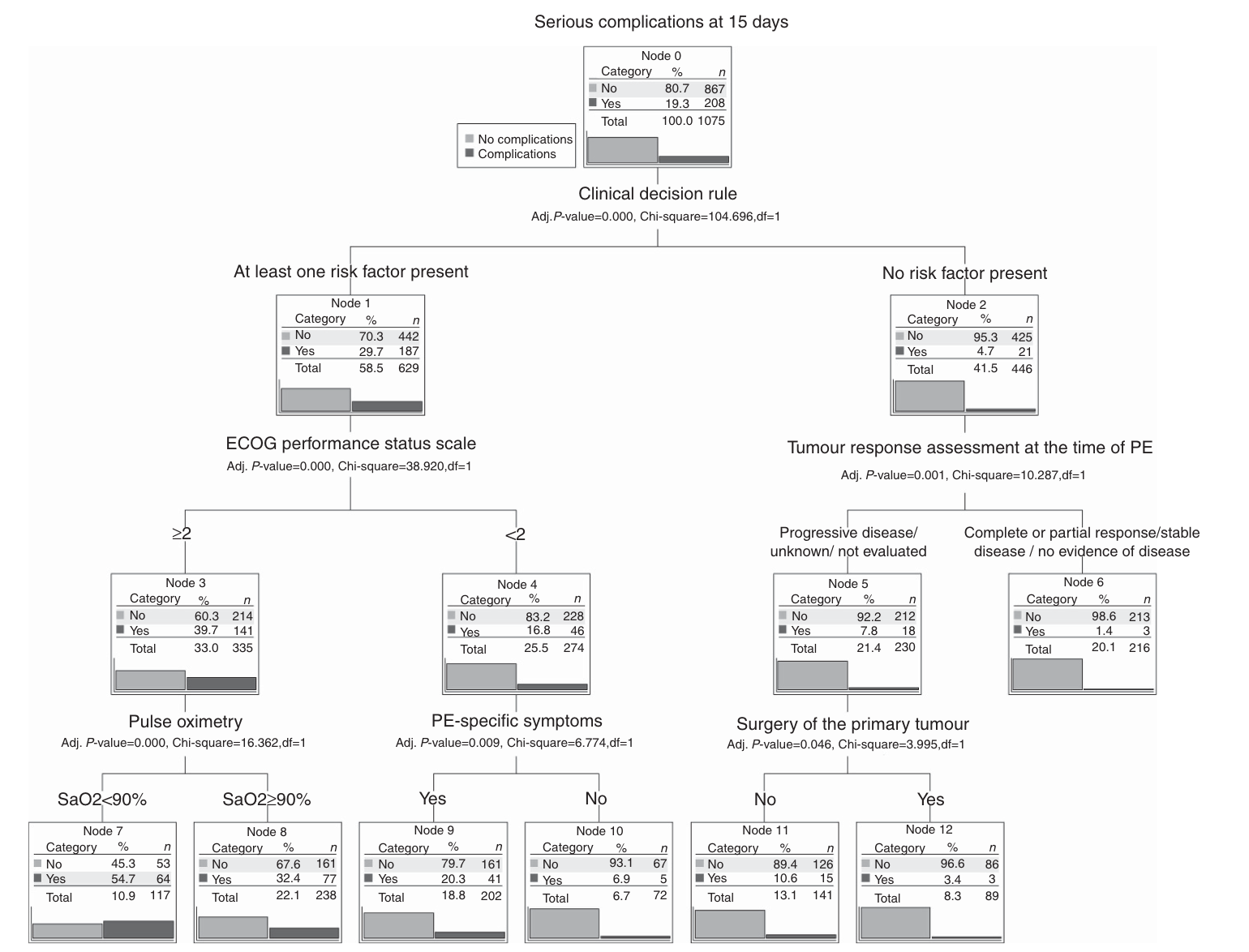

Figure 1: EPIPHANY Index for the prediction of serious complications

The short-term outcome (30 days) and the definition of an index useful for the prediction of severe complications in cancer patients with PE were the aims of the observational ambispective (retrospective and prospective) EPIPHANY study (Figure 1) [9,10]. In this work, patients were divided into three different groups:

- Patients with PE (43%);

- Patients with iPE and no symptoms (31%);

- Patients with iPE and symptoms (26%).

In this study, the majority of the patients were treated with LMWH as an anticoagulation therapy. The analysis revealed that subjects with unsuspected events had a better prognosis than those with suspected or unsuspected symptoms. Moreover, previous VTE episodes, low oxygen saturation, upper gastrointestinal cancer, poor performance status and tumor progression were associated with 30-day mortality. The last three factors were newly identified by the EPIPHANY study and may be useful in defining the 30-day prognosis [9]. In addition, the study highlighted that patients with iPE and no symptoms had a significant reduction of 30-day mortality risk with respect to PE patients and those with iPE and symptoms [9]. Starting from the EPIPHANY study, a second study brought the definition of the EPIPHANY index, based on a decision-making tree model, which allows classification of cancer patients with PE and iPE according to the risk of complications with 15 days [10]. The model is available here: https://www.prognostictools.es/

This index encompasses all the definitions of PE and has the practical aim of identifying patients at low risk of bad outcomes who do not need hospitalization. The EPIPHANY index is based on:

- The HESTIA criteria for PE outpatient management [11]

- Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status scale;

- Evaluation of tumor response prior to PE using RECIST 1.1 criteria;

- Previous primary tumor resection;

- Oxygen saturation; and

- The presence of PE-specific symptoms.

This tree model design is close to the evaluation of patients in a real-world setting, where diagnoses are made based on dichotomous choice (i.e., presence or absence of a specific symptom or feature, such as hypotension, acute respiratory failure, etc); therefore, it is of practical use in clinical management. The model is validated in a multicenter series [12].

In conclusion, iPE in cancer patients deserves the attention and treatment as a PE. Some factors, such as the type of cancer and its progression and the presence of metastases, may worsen the prognosis. Lack of symptoms could mask the need of specific care, and data strongly support the adoption of anticoagulant treatment in this population.

This article has been sponsored by an unrestricted educational grant from LEO Pharma A/S.

References

- Meyer G, Planquette B. Incidental venous thromboembolism, detected by chance, but still venous thromboembolism. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(2):2000028. doi:10.1183/13993003.00028-2020.

- den Exter PL, van der Hulle T, Hartmann IJ, et al. Reliability of diagnosing incidental pulmonary embolism in cancer patients. Thromb Res. 2015;136(3):531-534. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2015.06.027.

- Di Nisio M, Carrier M: Incidental venous thromboembolism: Is anticoagulation indicated? Hematology (Am Soc Hematol Educ Program) 2017:121-127, 2017.

- O’Connell CL, Razavi PA, Liebman HA. Symptoms adversely impact survival among patients with cancer and unsuspected pulmonary embolism. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(31):4208-4210. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.37.2730.

- den Exter PL, Hooijer J, Dekkers OM, Huisman MV. Risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism and mortality in patients with cancer incidentally diagnosed with pulmonary embolism: a comparison with symptomatic patients. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(17):2405-2409. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.34.0984.

- Jimenez D, Aujesky D, Moores L, et al. Simplification of the pulmonary embolism severity index for prognostication in patients with acute symptomatic pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170: 1383–1389.

- Qdaisat A, Kamal M, Al-Breiki A, et al. Clinical characteristics, management, and outcome of incidental pulmonary embolism in cancer patients. Blood Adv. 2020;4(8):1606-1614. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001501.

- Kraaijpoel N, Bleker SM, Meyer G, et al. Treatment and long-term clinical outcomes of incidental pulmonary embolism in patients with cancer: An international prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(20):1713-1720. doi:10.1200/JCO.18.01977.

- Font C, Carmona-Bayonas A, Beato C, et al. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of cancer patients with suspected and unsuspected pulmonary embolism: the EPIPHANY study. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(1):1600282. doi:10.1183/13993003.00282-2016.

- Carmona-Bayonas A, Jiménez-Fonseca P, Font C, et al. Predicting serious complications in patients with cancer and pulmonary embolism using decision tree modelling: the EPIPHANY Index. Br J Cancer. 2017;116(8):994-1001. doi:10.1038/bjc.2017.48.

- Zondag W, Mos IC, Creemers-Schild D, et al. Outpatient treatment in patients with acute pulmonary embolism: the Hestia Study. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(8):1500-1507. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04388.x

- Ahn S, Cooksley T, Banala S, Buffardi L, Rice TW. Validation of the EPIPHANY index for predicting risk of serious complications in cancer patients with incidental pulmonary embolism. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(10):3601-3607. doi:10.1007/s00520-018-4235-9